95

94

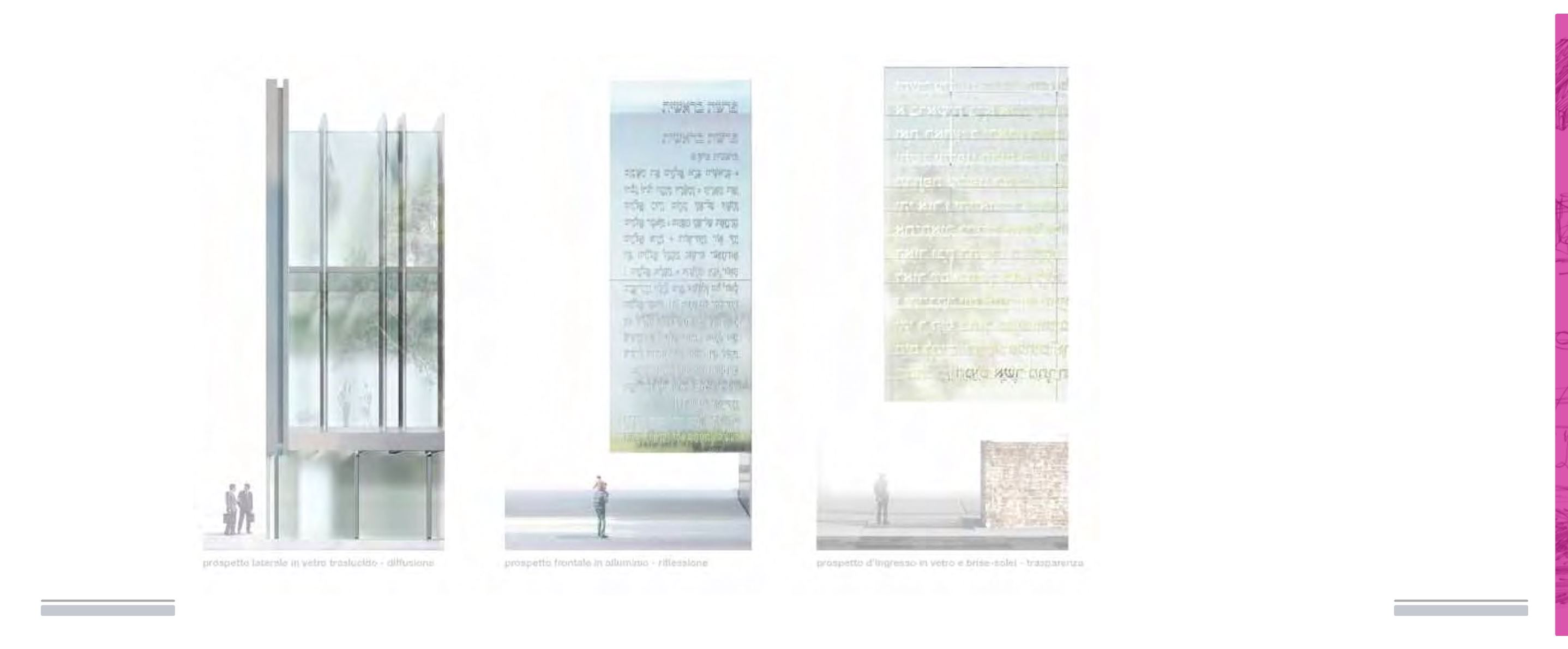

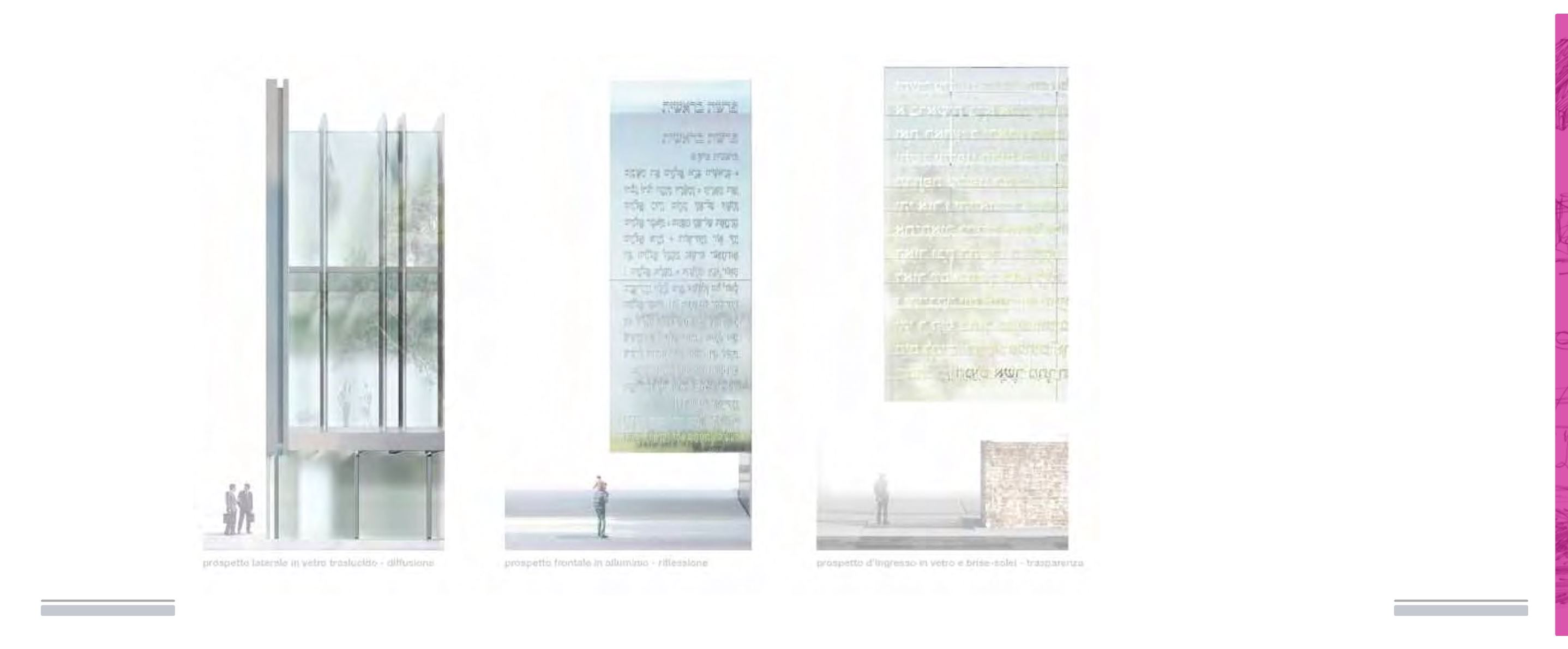

Il MEIS e la preesistenza

Fra le varie ipotesi di conservazione

della struttura esistente, il progetto

opta per quella più drastica che pre-

vede la sola conservazione dell’edi-

ficio C delle celle carcerarie e della

cinta muraria che comprende quel-

lo che era l’accesso al complesso pe-

nitenziario.

L’atteggiamento perseguito implica

una rigida selezione dell’esistente in

funzione della qualità dei manufatti

e non contempla la conservazione

come atteggiamento di non-scelta.

Coerentemente con questa scelta,

l’innesto di architettura contem-

poranea rifiuta ogni atteggiamen-

to mimetico: è invece occasione per

ricostruire gli equilibri spaziali ne-

cessari ai fini della rifunzionalizza-

zione del complesso. Il restauro si

configura quindi come un inter-

vento sostanzialmente semplice,

volto a tramandare al futuro la

vita fisica della fabbrica attraverso

la conservazione delle sue tracce

storico artistiche.

Cenni sull’allestimento

Come si è ormai affermato ovunque

nel mondo, un museo non è più sol-

tanto una raccolta di oggetti, anche

bellissimi, ma strumento e luogo per

comunicare significati, idee, me-

morie, cultura. Pochi importanti

oggetti significativi, opere d’arte, og-

getti d’uso fungono da potenti ri-

chiami alla storia e al tema del-

l’ebraismo, ma anche tabelle, dia-

grammi e immagini. Ecco, immagi-

ni, da aggiornare e adattare conti-

nuamente alla sensibilità del visita-

tore dell’epoca.

Fare un progetto multimediale per

un museo ricco di memoria storica

e di riferimenti iconografici come il

MEIS and the pre-existing

structure

Of the various options regarding

the existing structure, the project

selected the design which

conserves only block C with the jail

cells and the walls surrounding the

penitentiary complex.

This plan requires a rigid

examination of the existing

building for structural integrity and

discarding the attitude that

undertaking conservation work

means having no choice.

Consistent with this decision, the

use of contemporary architecture

refutes all mimetic approaches; but

is rather an occasion to recreate the

equilibrium necessary to make the

complex fully functional. The

restoration must be seen as an

essentially simple plan, in which the

physical life of the structure is

handed over to the future while still

conserving traces of its past.

Notes on the permanent

collection

As is generally agreed, a museum

is not only a collection of objects,

even beautiful ones, but an

instrument

and

place

to

communicate ideas, memories,

culture. While a collection of

important objects, works of art,

ordinary items, may serve as

powerful reminders of the

narratives and history of Judaism,

so do charts, diagrams and images.

Here, images are used to educate

and instruct the visitors.

Creating a multimedia design for a

museum rich with historical

memories and iconographic

references such as the MEIS

requires taking advantage of the

wide range of possibilities that

video affords.

On one hand there is the need to

organize and make accessible

historical materials such as film

footage, photographs, drawings,

papers of all kinds in the most

effective way possible. On the

other, there is the need to make

use of high impact large scale

moving images and scenes to aid

the spectator in quickly identifying

the main areas within the

architectural space and to allow

visitors to immerse themselves in

the atmosphere that these create.

These are two actions with

differing dynamic projections

which must be holistically

integrated.

The historical material, which may

be organized according archival

practice, also is capable, through

video, of offering the public a new,

more direct, means of involvement,

more immediate, in depth and

spectacular, without losing the

gravity of its informational value.

To achieve this, we can use “natural

interface,” which is at the forefront

of interactivity design. These are

interfaces that use natural means

(gestures, voice, touch, position) to

put the visitor in direct contact with

archival material. In practice,

interfacing a computer with digital

archival materials using video

support means that we can expand

and humanize the enormous

organizational ability offered by the

database. We can leaf through

digital books, call up photographs

of people or events with the sound

of our voices, touch photographs

to animate them and even hear

their stories. We may even take

away on our personal iPads copies

of the documents and photos that

interest us, by purchasing them as

downloads.

The architectural spaces may be

thematic, scenographic, of large

video images created appositely for

the space. We can bring to fruition

the enormous expressive means

that the last twenty years have

made available to us through

experimenting

with

video

environments and assembling

theatrical and musical works.