45

and all the other supporting

documentation.

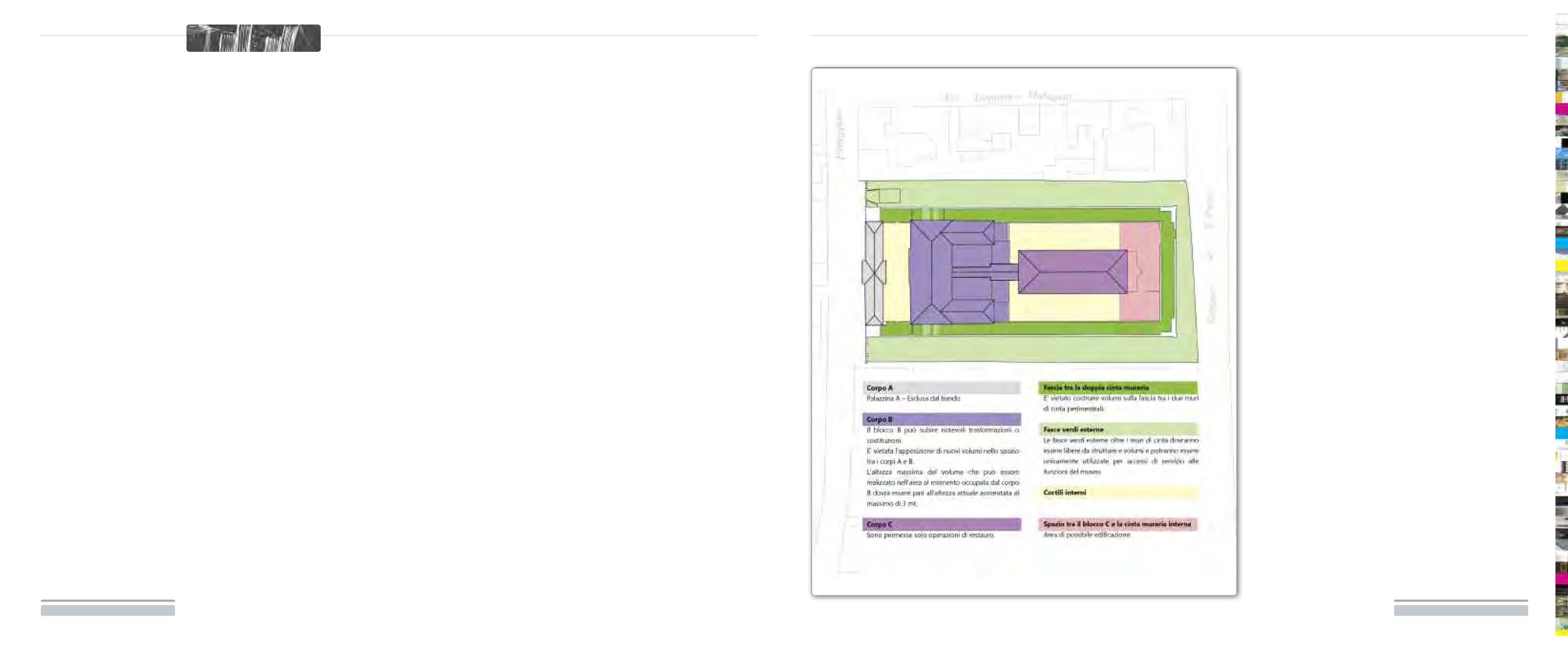

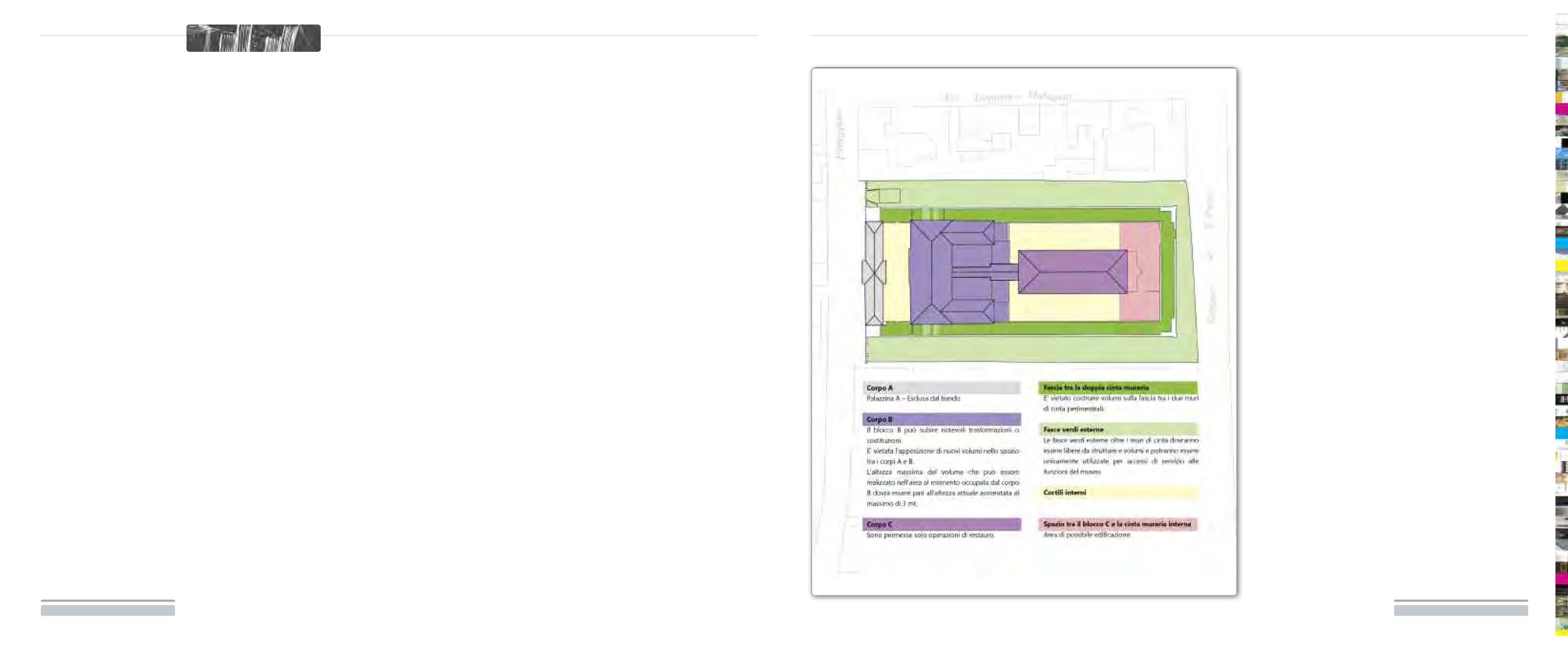

The objectives of the project are

clearly defined in article 6 of the

Document: a new entrance

structure for the jail; restoration of

the men’s cell block; preservation

of the boundary walls and open

spaces; the possibility of severe

modifications to the middle

building (block B); the articulation

of the internal spaces, and other

needs relating to the museum. The

working group, more than just

filling the needs as expressed by

the actors in the program, has

stimulated thinking to achieve a

synthesis that was useful in

guiding the project.

The historical and formal analysis

of the buildings identified the

men’s cell blocks (C) as a building

of significance and has determined

the restoration needs. The

entrance building (the palazzina)

on via Piangipane, which makes up

the image of the ex-jail as seen

from the city, was excluded from

the announcement. Of the

buildings that make up the

complex, the middle block (B),

which held the offices, sick bay

and women’s cells, was discovered

to be in poor structural condition,

and therefore of lesser importance.

This information, alongside the

awareness that the new museum

would be difficult to adapt into the

physical size and shape of this

building, led the push for a

significant transformation or

replacement.

On the other side, however, many

ongoing projects of the municipal

Previous experience led to

choosing a competition in one

phase open to all planners in the

European Union (article 5). Given

the multiplicity of the themes to

deal with, the client requested that

each design team would include

an expert in Jewish culture, an

expert in multimedia and

educational museum planning, an

expert in restoration and one in

planning sustainable architecture

(article 7), so that each one could

guarantee a full understanding of

the issues, and not least, the

maintenance and management

requirements of the structure.

Article 4 of the announcement

defined the objectives of the

competition: the reuse of the ex-

penitentiary in via Piangipane in

Ferrara and the adjacent spaces;

the redefinition of these spaces,

both open and closed; the

planning of new spaces and the

arrangement of the museum

itself. At the same time, the

announcement

asked

the

participants to approach the

theme of the museum, although

limiting this to the proposal

process. The museum has as “its

purpose

to

illustrate

the

uniqueness of Italian Jewish history

within the wider context of the

European and Mediterranean

setting, and, furthermore, to

promote

cultural

activities

designed to build on, for the

present and the future, the wealth

of knowledge, activities, ideas and

experience, resulting from the

more than two thousand years of

Jewish presence in Italy.” At

present, the quantity of objects

that are held necessary to tell the

history of the Jewish Italians is not

sufficient, and must be supported

by other instruments, such as

those provided by technology.

If on one hand, the form of the

open competition allowed many

proposals to be presented, it also

ensured that the threshold of

prerequisites for the professional,

financial,

technical

and

organizational requirements of the

participants (article 7) was derived

directly from an evaluation of the

overall costs of the museum,

thereby creating a strong barrier

and calling for the cooperation

between those with different skills.

In this way, the client was able to

guarantee the reliability and

qualifications of the selected

group. Even this was a reason for

censure

of

the

previous

announcement on the part of the

authorities

in

charge

of

regulations. Attempts to force a

lowering of the level of the

prerequisites

to

broaden

participation in the competition

did, in fact, fail.

CB

The Planning Directive Document

(Documento di Indirizzo

Progettuale, DIP)

The real heart of the design

competition is the Planning

Directive Document (DIP in Italian),

the key that specifies the needs of

the client and therefore guides the

designers. It was from the work of

preparing this document that

came about the announcement

44

disposizioni dell’articolo 74 della

Direttiva della Comunità Europea

n. 18 del 31 marzo 2004.

Nel caso del MEIS di Ferrara, si era

inizialmente optato per questa

procedura. Il tema è, infatti, di

notevole complessità e il bando

richiede ai concorrenti due distinte

progettazioni: il restauro ed ade-

guamento del complesso e l’idea

di allestimento del museo. Lo

sforzo che i progettisti avrebbero

dovuto sostenere per approfon-

dire un tema così complesso era

sembrato eccessivo per essere

affrontato nel suo insieme senza

potere avere la garanzia, tra l’al-

tro, di un rimborso spese. Tuttavia

le vicende dei casi già citati hanno,

alla fine, indotto a scegliere un

concorso in un’unica fase.

Sintesi del bando

Gli aspetti caratterizzanti dei

bandi, definiti dalla stazione

appaltante, sono nel dettaglio:

l’individuazione del tipo di con-

corso e dei suoi obiettivi, e la defi-

nizione dei requisiti di tipo profes-

sionale, economico-finanziari e

tecnico-organizzativi richiesti ai

partecipanti.

Le esperienze pregresse hanno

indotto a scegliere un concorso ad

una sola fase aperto a tutti i pro-

gettisti della comunità europea

(art. 5). Vista la molteplicità dei

temi da affrontare la stazione

appaltante ha richiesto che nel

gruppo di progettazione venissero

inclusi un esperto di cultura

ebraica, un esperto nella progetta-

zione di musei multimediali e

didattici, un esperto in restauro e

uno in progettazione sostenibile

degli edifici (art. 7), affinché cia-

scuno potesse garantire la piena

comprensione dei temi trattati,

non ultime le necessità di manu-

tenzione e gestionali della strut-

tura.

L’art. 4 definisce gli obiettivi del

concorso: il riuso del carcere di via

Piangipane di Ferrara e degli spazi

accessori, la ridefinizione degli

spazi aperti e chiusi, la progetta-

zione di nuovi spazi. Al contempo,

il bando chiede ai partecipanti di

affrontare anche il tema dell’alle-

stimento museale, seppure limi-

tandolo alla fase propositiva. Il

museo «ha come finalità istituzio-

nale quella di illustrare l’originalità

della storia ebraica italiana nel

contesto del più vasto ambito

europeo e mediterraneo e, dall’al-

tro, promuovere attività culturali

volte a mettere a frutto, per il pre-

sente e per il futuro, il patrimonio

di saperi, attività, idee ed espe-

rienze, testimoniate dalla più che

bimillenaria presenza ebraica in

Italia». Non essendo al momento

disponibile una sufficiente colle-

zione di oggetti si è ritenuto

necessario fornire l’indicazione

che la narrazione della storia degli

ebrei italiani dovesse essere sup-

portata da altri strumenti, tra cui

la tecnologia.

Se da un lato la forma del con-

corso aperto ha consentito a molti

di presentare una proposta pro-

gettuale, le soglie dei requisiti di

tipo professionale, economico-

finanziari e tecnico-organizzativi

introdotte (art. 7), che derivano

direttamente dalla valutazione del

costo complessivo del museo, ha

creato un forte sbarramento e invi-

tato all’accorpamento di studi

diversi. La stazione appaltante ha

potuto garantirsi in questo modo

della affidabilità e delle capacità

del gruppo prescelto. Anche que-

sto era stato un motivo di censura

di precedenti bandi da parte delle

autorità preposte al controllo di

regolarità. Il tentativo di forzare la

norma abbassando il livello dei

requisiti per consentire la parteci-

pazione ai concorsi più ampia pos-

sibile era, infatti, fallito.

CB

Il Documento di Indirizzo

Progettuale

Il cuore vero del concorso di pro-

gettazione è il Documento di Indi-

rizzo Progettuale (DIP), momento

centrale di verifica delle esigenze

della committenza e, allo stesso

tempo, di orientamento per i pro-

gettisti. È dal lavoro di prepara-

zione di questo documento che

discende il bando stesso e tutti gli

altri documenti.

È il DIP che definisce con chiarezza

all’art. 6 gli obiettivi del progetto:

un nuovo sistema di accesso al

carcere, il restauro del corpo delle

celle maschili, la salvaguardia dei

muri di cinta e degli spazi aperti, la

possibilità di profonde modifiche

del volume intermedio (corpo B),

l’articolazione degli spazi interni e

le esigenze di natura museogra-

fica. Il gruppo di lavoro, più che

compilare le esigenze espresse

dagli attori coinvolti nel pro-