133

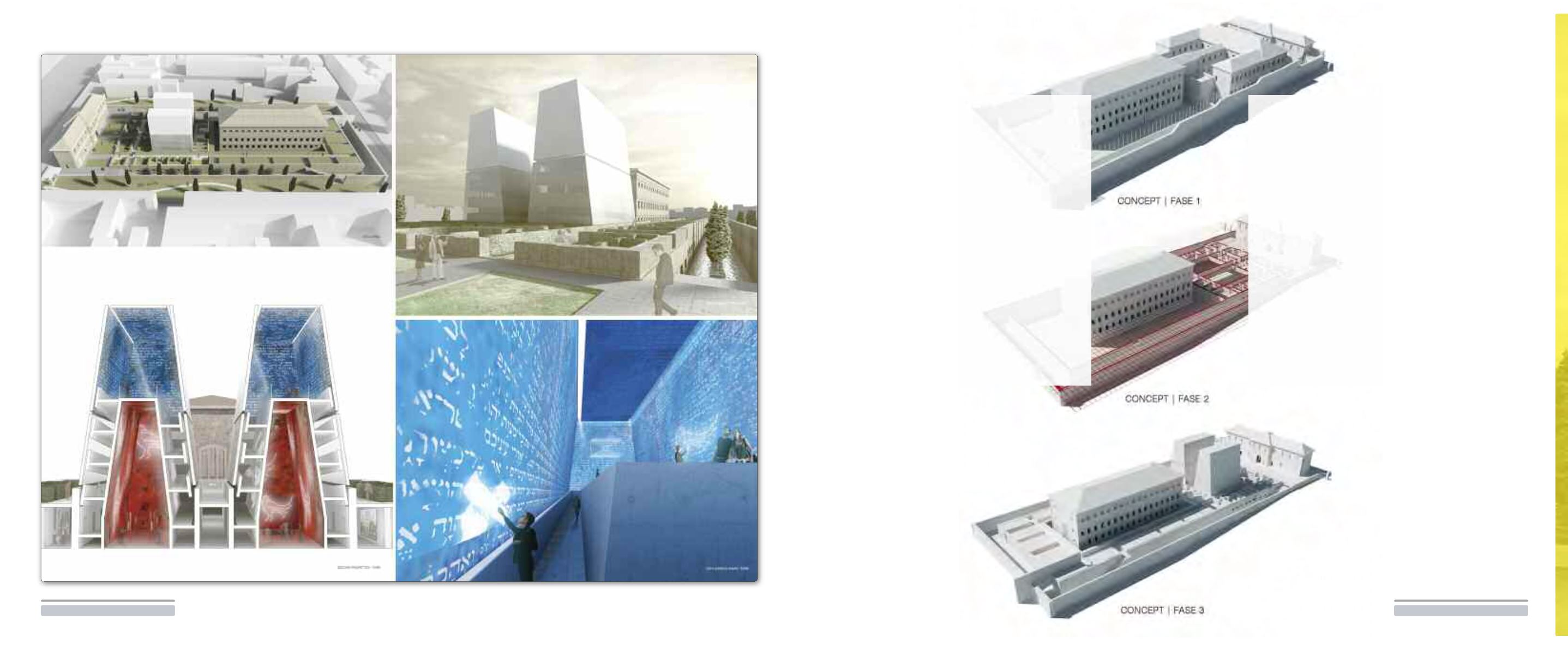

Casualmente, a livello planimetrico

e tipologico, l’impianto carcerario

– una struttura dentro un recinto –

ci offre un potenziale, una possibi-

lità di sublimazione; questo ci ri-

porta, come metafora, al tema del

luogo sacrale della tradizione, al

tema del tempio all’interno di un

recinto sacro.

Lo smontaggio lascia ben visibile la

muratura, sopra il piano di calpe-

stio, ne risulta un

podium

che di-

viene la base della struttura del

museo, alla quota della città, un

giardino pensile aperto alla città. Il

giardino pensile, come un

hortus

conclusus

, si collega alla darsena

passando tra le “rovine” dell’edifi-

cio demolito e al di sopra dei nuovi

spazi. Dallo spazio libero delle corti

sorgono due nuove torri che emer-

gono dal

podium

. Due torri dia-

fane, traslucide, dialogano con la

città, segno evidente e manifesto

della presenza del nuovo museo.

Sulla parte più elevata delle torri sa-

ranno proiettate immagini che se-

gnalano il dinamismo del museo e,

la notte, come grandi corpi lumi-

nosi, segneranno la sua presenza.

Un muro, come una lama calata

sul perimetro del carcere, segna

l’ingresso al MEIS, un segno forte

che marca l’intervento di rottura

del recinto che per decenni è stato

sinonimo di inaccessibilità e soffe-

renza.

Il percorso museale si sviluppa se-

condo due tipologie: una verticale,

il museo dell’ebraismo, e una oriz-

zontale, il museo degli ebrei in Ita-

lia.

È un luogo dinamico d’incontro, di

sperimentazione artistica, cinema-

tografica e teatrale, di rappresen-

tazione a confronto del passato e

del presente con prospettive

verso il futuro.

Gli oggetti esposti in queste se-

zioni “dinamiche” sfuggono alla

musealizzazione tradizionale,

perché correttamente contestua-

lizzati in una cornice didattica che

permette di comprenderne la

funzione per cui essi sono stati

pensati e che determinano ancor

oggi il loro utilizzo

A tal fine acquistano grande im-

portanza le tecnologie museolo-

giche attuali che consentono di

proporre, accanto agli originali,

copie virtuali di oggetti con cui il

visitatore può interagire (

Tangible

User Interface

), divenendo, da

mero “fruitore”, attore del pro-

prio percorso.

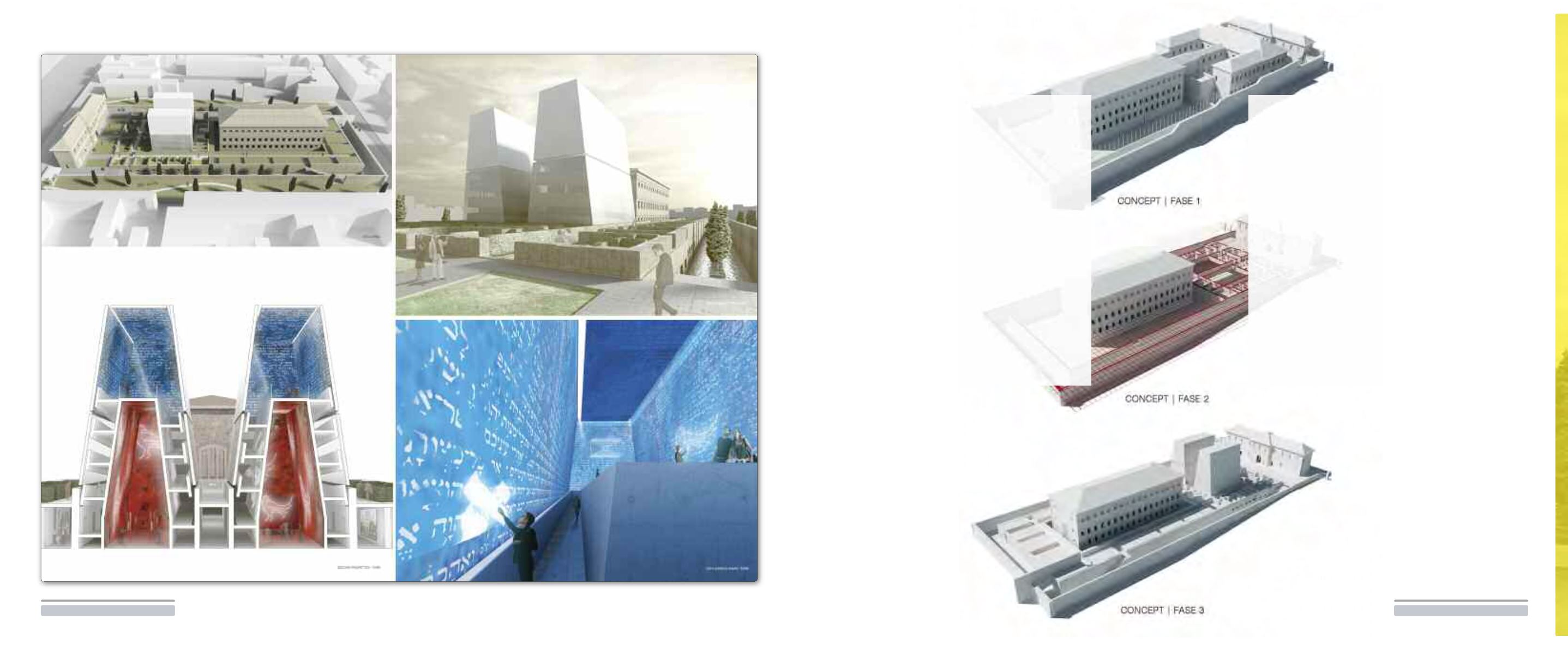

offers possibilities, a potential for

sublimation; this is carried over,

like a metaphor, into the theme

of the traditional sacred place,

the theme of the temple within a

sacred boundary.

The dismantlement leaves the

walls clearly visible. There will be

a platform above the walkway

which becomes the base of the

museum structure, set at the

same level as the city, with a

hanging garden facing the city.

The hanging garden, as a

hortus

conclusus

(an enclosed medieval

garden) connects to the harbor

by passing between the “ruins” of

the demolished buildings and

above the new open spaces.

From the space opened up by the

courtyards will arise two new

towers emerging from the

platform. Two sheer buildings,

translucent, that dialogue with

the city, providing a clear and

visible manifestation of the new

museum. Pictures will be projected

on the uppermost part of the

towers showing the dynamism of

the museum, and at night, these

brightly lit bodies proclaim their

presence.

A wall, like a blade dropped on the

perimeter of the jail, marks the

entrance to the MEIS, a strong sign

visibly breaking the walls that were

synonymous with confinement

and suffering for decades.

The route through the museum

unfolds on two levels: one vertical,

the museum of Judaism, and the

other horizontal, the museum of

Italian Jewry.

It is a dynamic meeting place, of

experimentation in the arts,

cinematography and theatre, of

representing and confronting the

past and the present while looking

forward into the future.

The objects in this “dynamic”

section escape from traditional

museum formats because of

correctly contextualizing them in a

didactic frame, giving an

appreciation of their intrinsic

function and identifying how they

are used today.

To this end, it is of great importance

to acquire the museum technology

for the display of original items

alongside virtual copies with which

the visitors can interact (Tangible

User Interface), making them not

mere spectators but active

participants in their visit.

132