Montagnola del Barchetto and the Delizia della Rotonda

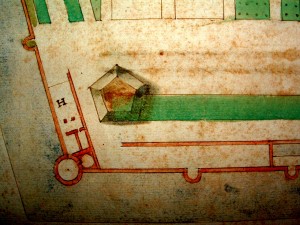

Dettaglio della Punta della Montagnola in sezione, pianta seconda metà del XVI secolo (Modena, Archivio di Stato, Mappario Estense, Topografie di città, 66 ©)

The Rotonda, or Delizia della Montagnola: one of the most interesting and charming Este residences, built in Rossetti's Torrione di Francolino.

A defensive tower turned palace

Documented as early as 1529, the raised section of land visible today is all that's left of the three ‘knights’ - that is, artificial mountains built by Duke Alfonso I d’Este (1476-1534) in three strategic points on the city walls: the Montagna di Sopra to the south-west, opposite Belvedere Island, watching over the river that lapped the city; the Montagnola del Barchetto, originally pentagonal in shape, to the north-east right next to the Torrione di Francolino; and the Montagna di Sotto, also known as the Montagna di San Giorgio, the most imposing of them all, built on a south-eastern bulwark of the same name. Conceived of as military tools (as lookout points and for the placement of cannons), the artificial mounds were turned into ‘mountains of paradise’ under the rule of Ercole II d’Este (duke from 1534 to 1559), covered in herbs and floral essences, standing out for the presence of water brought there via hydraulic devices. From these springs of life, water flowed down the slopes towards brick-trimmed streams and, with all its force, kinetic and cathartic, it entered the lands of the Barchetto via the Certosa, i.e. the park with gardens and animal enclosures exclusively used by the duke and his court.

In February 1550, Ercole II d’Este began transforming Rossetti's Torrione di Francolino into a veritable house, called the Rotonda. That year, poet Vincenzo Brusantino penned its praises (Brusantino 1550, XVII, 91-92):

Here is the Barchetto, where valiant

knights will be able to fiddle about undisturbed

to handle horses and open roads

to run with lances and use their swords.

The large tower, which surrounds

in the guise of a tall palace,

was called the Rotonda

at the side it adorns, together, and the knight.

The room is so pleasant and playful

that all worries are lazily forgotten

and delightful scents arrive from far away:

citron, orange and other flowers

This lost building is shown on a map from 1569, presenting the external appearance of the palace as it was during a large naval tournament, L’Isola Beata, held in the moat that surrounded the terreplein of the Montagnola on the night of 25 May of that same year. This wonderful drawing attests to a theatrical stage made by multiple talented court artists and craftsmen, including Marcantonio Pasi, who came up with the large rustic building to the left, and Pirro Ligorio, designer of the water machines and sea monsters.

The documents found a few years ago by Andrea Marchesi make it possible to confirm the architectural authenticity (and permanence) of the structure found on the right side of the drawing. Seen from the outside, the massive defensive tower and the segment to the right present façades divided into regular intervals by long half pilasters with Doric capitals, separating windows and niches. Below them are faux framed rectangular panels in relief. It is the ultimate triumph of false appearances. Everything seems made of marble, but the bare stone here was recreated entirely with plaster, just as the appearance of depth is created by fading colour fields.

The probable location of Ercole d’Este's octagonal bedroom inside the large circular defensive tower - with a vaulted ceiling frescoed by Camillo Filippi with the feat of Occasione e Penitenza or with the ‘round room’, depicting one of the labours of mythological Hercules painted by Filippi also - helps us fully grasp a fundamental personality trait of the fourth duke of Este: from Marcus Fabius Quintilianus to Petrarch, and often found in hagiography, only the solitude and peace of nature can elevate the spirit to a dimension of high moral quality. And it was precisely the view from the large windows of the Rotonda that allowed Ercole to enjoy the silence of the vast and wooded Barco.

The landscape was in dialogue with the building, incorporating and amplifying its symbolism. The outside walls of the structure facing the gardens and those of the loggia were completely frescoed with landscapes by Lucas van Leyden, a collaborator of Giulio Romano in the Gonzaga work yards of Marmirolo and Palazzo Ducale, also active in Ferrara after 1545. Artificial streams irrigated geometric gardens of narcissus and oleander, framed by boxwood and blackberry bushes, while trail intersections were marked by dozens of pots with orange and lemon trees. To the west, towards the Belfiore residence of Cardinal Ippolito II d’Este, long, ample fences allowed ostriches to run free: this spectacular, oriental element was a must, turning the site into a truly idyllic place.

Even the least-imaginative visitor would have been thrilled and moved in such an original structure. Viewed from the outside, the Rotonda appeared to be suspended over the reflective pool that lapped along the entire system of walls: a fairy-tale of a building, as light as a feather. Could there be a better stage for the magical theatrical productions of the Isola Beata?

A passage in the letter that Teodoro da San Giorgio sent to the Duke of Mantua on 20 April 1580 is a perfect example of what the Montagnola represented under Alfonso II d’Este, Ercole’s son. The courtier, in informing Guglielmo Gonzaga about the daily duties of the court of Alfonso, says that the day prior, a cheery group of nobles, including his son, Vincenzo Gonzaga, went to see a play at the court after returning from the Montagnola, ‘where there were loves and ladies, knights and arms’. Only such a skilled quotation of the very beginning of Orlando Furioso could flawlessly capture the chivalrous and epic-courtesan values that distinguished the lordship of the last Duke of Ferrara, culturally shaped from a young age at the court of the French king.

The cool temperature of the Rotonda seems to have drawn a good part of the numerous court of Alfonso there in the summer months, lounging about in the delight of long banquets, musical performances and horseback tournaments of the type Ariosto wrote about. It is no coincidence that, in May 1581, Torquato Tasso wanted to present his pastoral fable, Aminta, to a prestigious audience of Italian princes there.

Destruction

The Rotonda was completely razed to the ground in 1616, creating a gap, an open wound, in the architecture, in addition to causing aesthetic-panoramic and historic-artistic damage which remained ingrained in the minds of eyewitnesses, including Alberto Penna:

The Rotonda palace is no more, having been torn down to its foundations. The Montagnola itself is no longer at its normal height, there are no more groves, no more gardens, no more areas, no more roads, no woods, no park, no fruit trees, no flowers, no hedges, no bushes, no pots, no citrons, no olive trees, and no more than a meadow, a pasture, a barn, a heard of cattle, to which use the aforementioned plains have been converted and destined, in which you can see the last few leftovers of a few elms in the middle, showing the remnants of two large roads that went to the gate, that feeds into the street of Santa Lucia, and, of the other said park, today it too has been deformed to the same degree as the rest.

Of the ancient complex, only the opening of an icehouse (nestled in a small elevation of land) and what's left of the Montagnola remain. Climbing up the hill, and looking out towards Castello Estense, visitors can see the ample presence of green land, which has been left untouched since the days of the Addizione Erculea (1492).

The echo of the Montagnola

According to the writings of Francesco Avventi, visitors noticed a unique acoustic effect near the Montagnola even in the early nineteenth century:

Following the city walls, on this side, coming to a point indicated by a small marble baluster, where a marvellous echo distinctly repeats up to two entire eleven-syllable verses when spoken aloud and with celerity. And seeing as the echoing corner is found at quite a distance from the experimenter, he thus has the time to clearly hear the repetition of the words he has spoken, making this echo one of the most specious and distinct, among all those known today.

Bibliography

- Francesco Brusantino, Angelica Innamorata, per Francesco Marcolini, Venezia 1550

- Alberto Penna, Descritione della porta di San Benedetto della città di Ferrara, Mattio Carodin, Padova 1671

- Francesco Avventi, Il servitore di piazza. Guida per Ferrara, Tipografia Pomatelli, Ferrara 1838

- Andrea Marchesi, Grotte, Montagne e fontane estensi. Natura artificiata nella Ferrara del Cinquecento, in Gianni Venturi, Francesco Ceccarelli (a cura di), Delizie in villa. Il giardino rinascimentale e i suoi committenti, Olschki, Firenze 2008

- Andrea Marchesi, Originalità architettoniche e nuove figurazioni decorative nelle residenze ferraresi di Ercole II d'Este: il “real palagio” di Copparo e la “vaga” Rotonda, in Francesco Ceccarelli, Marco Folin (a cura di), Delizie estensi. Architetture di villa nel Rinascimento italiano ed europeo, Olschki, Firenze 2009

- Andrea Marchesi, Delizie d'archivio. Regesti e documenti per la storia delle residenze estensi nella Ferrara del Cinquecento, Tomo II, Dimore urbane, Le Immagini edizioni, Ferrara 2015

Fototeca

Related Themes

Compiling entity

- Assessorato alla Cultura e al Turismo, Comune di Ferrara