Benvenuta, Nuta, Ascoli (Ferrara, 1873-1941)

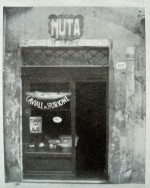

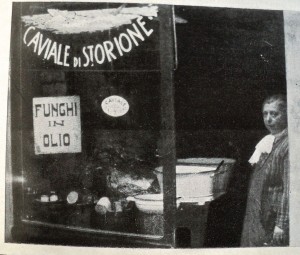

Benvenuta Ascoli portrayed in front of her shop on Via Mazzini. Photograph from Rivista di Ferrara, no. 7, year III, July 1935.

Nuta Ascoli was the owner of a well-known kosher restaurant in Via Mazzini. Among her specialities were buricche and caviar from the Po, which was also exported abroad. Giorgio Bassani mentions it in his "Garden of the Finzi-Continis", changing its name to Bathsheba of Fano.

1. The ‘delicacies’ of Nuta

At number 62 of Via Mazzini until the 1930s, Miss Benvenuta Ascoli had her kosher delicatessen shop. She was known to many as ‘la Nuta ‘, daughter of Lodadio Ascoli, and resided with her sister Elisa in the house-laboratory not far away, in Via della Vittoria.

Hers was even then a shop of other times, "a very small shop of Jewish delicacies" (Bassani Liscia 2000, p. 37). Among the specialties of Nuta: the ‘bongola’, a kosher reinterpretation of salama da sugo made with beef, salami and goose ham. But Nuta Ascoli was especially famous for buricche and caviar from the Po.

2. Buricche (or buricchi)

The origin of this stuffed pasta probably dates back to the emigration of Sephardic Jews fleeing from Spain and Portugal in the sixteenth century. The name could derive from the Turkish boreka, while the sweet or savoury filling recalls the Spanish and Portuguese empanadas: for the sweet one, chopped almonds with a bitter almond, sugar and lemon peel are used, while the savoury one can be made with boiled veal or beef, chicken, or livers.

3. The original recipe of Cristoforo da Messisbugo

The history of Po caviar begins with the recipes prepared by Cristoforo da Messisbugo for the court of Alfonso I d'Este and then of Ercole II d'Este, in particular that of the ‘caviaro per salvare’ contained in the "Libro novo in which it is taught to make any kind of living", published in the mid-sixteenth century. Messisbugo writes: "Take sturgeon's eggs, and the more black they are, the better; and separate them on a table with the rib of the knife, clearing them well from the flocked ones, and weigh them, and for every 25 pounds of eggs, you will lay 12 and a half ounces of salt, that is, one and a half ounces per pound of eggs". After leaving them like this for one night and lying on a wooden plank with sides, "you will put them in the oven that is honestly hot, for the space of two paternosters; then you will dig them out and mix them very well with a wooden pallet and put them again in the oven, leaving them as mentioned above". For the caviar to be preserved, the Messisbugo recommends placing it on top of "well fired" stone vases and "when it is very hot, for every day you win you will have to remove that loom that you will give upstairs: and you will add a little oil".

4. The dispute of Isacco Lampronti

We find it two centuries later in "Pahad Izhak" (Fear of Isaac), the talmudic encyclopaedia by Isaac Lampronti published in Venice between 1750 and 1753. Under the heading ‘fish’ (daghim) the learned rabbi from Ferrara discusses the problem of the sturgeon's kasherut (Jewish food standards): the problem is that the sturgeon has fins as prescribed by Leviticus, but the scales are bony and therefore more like plates, moreover not easy to remove, than scales of simple removal as indicated by the Law. Lampronti compares himself with older rabbis and establishes that in Ferrara the consumption of the "copese", that is, the sturgeon copice, one of the varieties then widespread in the Po, is not prohibited.

5. Nuta caviar

This brings us to Lodadio Ascoli, the father of Nuta, who at the end of the nineteenth century in his small shop in Via Mazzini, prepared cooked caviar with a recipe perhaps derived from that of Cristoforo da Messisbugo in the sixteenth century. The workshop where Benvenuta Ascoli prepares caviar is on the ground floor of the house in Via della Vittoria: “The oven is ready and Nuta takes the box and entrusts it to a lad who pushes it into the very hot oven. Goodbye box, I think, and anyone who saw such an operation. La Nuta, who guessed my mind, reassures me by telling me not to be afraid of the box because it is of such a special wood that has not burned since 1860 " (Canella 1935, p. 322). Nuta does not know where her father learned; she can produce a few quintals a year and also export it to Switzerland.

"The trouble is that Nuta alone knows the manufacturing secret by heart and if, by combination, she were to have a moment of amnesia, goodbye to figs, indeed, goodbye to caviar. But there's worse! That Nuta has no intention at the moment of handing down the formula of preparation to posterity" (Canella 1935, p. 322). This was not the case: during the research for "La Signora del Caviale" (Florence, Cult Editore) Michele Marziani discovers that the notary and gastronomist from Ferrara Roberto Brighenti found the Nuta caviar recipe at the Jewish Community of New York and on his death he handed it down to his cook Giuseppina Bottoni.

6. The rebirth of an ancient gastronomic tradition

Just during one of the presentations of Michele Marziani's book Giuseppina Bottoni meets Cristina Maresi, who together with her husband runs an agritourism in Runco, near Portomaggiore, near Ferrara. Now the sturgeons and their eggs were missing, because since the 1950s, mainly due to pollution, the Po sturgeon is now only a memory. Giuseppina and Cristina found a breeder in the Marca Trevigiana who decided to help them: this is how the recipe for caviar from Ferrara was reborn.

7. Quotes

"‘Nuta’?! but yes, you have seen it many times that little shop in Via Mazzini, a little one, rather dark. I think it is the only shop that still retains all the colour of the Ferrarese Ghetto. Above the narrow door, which almost hides in the wall, there's a red-brown plaque that says‘ Nuta ’. Looking through the glass of the exhibition you can see little catinels, frying pans, strange focaccia, rare salami and behind all this the darkness. It is not difficult that on the door of the shop you happen to notice a little woman with a round and nice face who looks through two round eyes of indefinable colour. Well, this figure is Nuta, who makes caviar and goose salami. You can enter his shop and then you realize that it is different from any other: an old, very old counter, objects as they are found in our first and distant memories. [...] It is enough to stay at the Nuta for half an hour, even less, and slowly without realizing it you are transported back in time: Via Mazzini becomes the Ghetto where the industrious Jews of Ferrara traded and lived familiarly".

Arlodo Canella, Storione più Nuta uguale a caviale, in “Rivista di Ferrara”, no. 7, year III, July 1935, p. 322.

Bibliography

- Canella, Aroldo, Storione più Nuta uguale a caviale, in «Rivista di Ferrara», III, 7, Luglio, 1935, Ferrara, pp. 320-322

- Bassani Liscia, Jenny, La storia passa dalla cucina, ETS, Pisa 2000

- Rundo, Joan (a cura di), La cucina ebraica in Italia. Oltre 200 ricette della tradizione, Sonda, Casale Monferrato 2003

- Marziani, Michele, Il caviale del Po, una storia ferrarese, 2G editrice, Ferrara 2013

Fototeca

Related places

Related Subjects

Compiling entity

- Istituto di Storia contemporanea di Ferrara

Author

- Federica Pezzoli

- Sharon Reichel