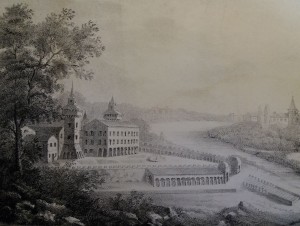

The Belvedere Palace and Island (destroyed)

Parte orientale dell'isola di Belvedere, con palazzo, stampa ottocentesca (Ferrara, Biblioteca Comunale Ariostea, H.5.1, n. 43 ©)

The only river island close to Ferrara, the Belvedere was actually one of the most original and pleasant places in all of Renaissance Italy. Alfonso I d'Este transformed this strip of land into a paradise worthy of a prince, with art, nature and sensory delights.

Historical notes and architectural characteristics

Situated on the ancient course of the River Po not far from the south-western vertex of the city walls, the ancient site of the island occupied the expansive area which now lies between the roads of Via San Giacomo, Via Darsena, Via Mulinetto, Via Saragat, Via Arginone and Via Maverna, now defined by the railway lines of the nearby station. The clean air, abundant water and the presence of extensive, pristine woodlands were the main reasons that propelled Alfonso I d’Este (duke from 1505 to 1534) to turn this strip of water-surrounded land into an exclusive residence, called the Belvedere, with private buildings that could be adapted to receive illustrious guests on special occasions.

Building at the site began in 1513 and, in less than a decade, a complex sprung up comprised of geometric gardens, fountains, baths, water displays, menageries for exotic animals and, above all, an intricate system of buildings on the eastern end, centred around a great palace. With a longitudinal layout, the palace featured quadrangular towers, a large open courtyard with open galleries and several spaces with rich interior and exterior decorations. Exalted by the leading literary figures of Ferrara in the early sixteenth century (even Ludovico Ariosto refers to the palace in the third edition of his epic poem Orlando Furioso), for an entire century the Belvedere island served as a stage for the power of the Este family, often hosting a number of important theatrical productions, including Torquato Tasso’s Aminta (1573) . One of the first references to the Belvedere (also called the Boschetto) ‘in the middle of the Po’ is found in a letter sent by architect Biagio Rossetti to Cardinal Ippolito d’Este in November of 1513. In it, he references the work being done to level the earth, remove weeds and subsequently plant of thousands of oak and poplar trees, whose shady branches would cool the open terraces in multiple places, used for summer banquets.

About one kilometre long, this almond-shaped island covered about 24 hectares: from the estimate made by a consultant named Benmambri in 1598, we know that the eastern point containing the residential dwellings was surrounded by a curtain wall with embankments and crenellations. It was over 6 m tall and embellished by a marble strip along the base, where iron gates affixed to the interspersed pillars encircled the rest of the land. The entire upper part of the enclosure featured decorative gilded bronze butterfly weather vanes resting on flaming orbs, i.e. the ‘fluttering grenades’ of Alfonso I d’Este's heraldic livery, completed in 1516. Among the items that most amazed visitors were the monumental fountains, one in bronze in the shape of a branched tree trunk placed in the middle of a large Carrara marble pool (in the meadow just before the main façade of the palace), the other in Istrian stone in the guise of a ‘big rock’, i.e. a small mountain, set in a tree-lined recess in the back. Both of the fountains were completed by Giovanni Andrea Gilardoni and his companions Gregorio and Alfonso Lombardi (the latter being one of Emilia’s most famous bronzesmiths and sculptors) between 1517 and 1519. In addition to the fountains, the ingenious duke had another three structures built, each equipped with hydraulic mechanisms that included underground pipes to release sudden bursts of water and a large circular reservoir (built between 1519 and 1523). A falsely immobile wooden bridge crossed the reservoir that had a device which, if triggered suddenly and in certain circumstances, soaked the stunned passer-by to the amusement of all. There were also ‘bath rooms’ connected at the rear of the dwelling, made up of small rooms with stepped tubs and barrel vaults to maintain the humidity and the warmth created by the copper furnaces.

A land of sensory pleasure and physical well-being restored after the strain of politics and leadership, the Belvedere was truly a theatre dedicated to the magnificence of Alfonso d’Este, one of the most skilled patrons of the European Renaissance. According to humanist Scipione Balbo, as soon as they set foot on the island, visitors could admire the front of the palace, decorated with paintings, while a wall with a fresco depicting animals ran around the area to the rear, probably those that populated the enclosure to the west. In 1540, a survey of the enclosure counted over 200 animals of various species (including ostriches, fallow deer, bucks, roe deer, tabby cats, porcupines and peacocks) living there. The internal decorations on the fireplaces in the bathrooms and the exterior decorations on the merlons and façades with landscape scenes can be attributed to Tommaso da Carpi and Albertino Grifo, both steadily present at the work yard from March 1514 until spring 1519. At that point, Dosso Dossi took over, mainly seeing to the task of embellishing the interior of the private chapel. The entire dwelling was painted and re-painted over the following decades. In particular, the surviving documentation notes that the leading artists of Alfonso II’s court added their touches to the building in the 1580s and 1590s, especially Ludovico Settevecchi, Bartolomeo Faccini and Leonardo da Brescia.

Written reports from the late sixteenth century mercilessly document the fatal destiny of the island after the Este family fled the city (1598), removing the paintings, marble trim, tapestries and other precious furnishings kept in the palace. Little by little, the structures were plundered by the pope’s rather rough-around-the-edges soldiers, as were the gardens, trees and animals in the enclosure: stones, marble, columns and even a spiral staircase coming from the looted Belvedere Island were then used to finish building the convent for the church of Santo Spirito, in what is now Via Montebello.

The curtain of history fell on this idyllic place a short time after the devolution of Ferrara to the Holy See: between 1608 and 1618, the island – and a vast part of the surrounding urban and suburban area were completely razed to make room for the new papal citadel (demolished between 1859 and 1865).

Bibliography

- Bruno Zevi, Biagio Rossetti architetto ferrarese. Il primo urbanista moderno europeo, Einaudi, Torino 1960

- Gianni Venturi, Un’isola tra utopia e realtà, in Andrea Buzzoni (a cura di), Torquato Tasso tra letteratura, musica, teatro e arti figurative, Bologna 1985

- Francesco Scafuri, Le mura di Ferrara. Un itinerario attorno alla città, tra storia ed architettura militare, in Maria Rosaria Di Fabio (a cura di), Le mura di Ferrara. Storia di un restauro, Minerva, Bologna 2003

- Francesco Ceccarelli, Forme degli insediamenti estensi nel Ferrarese tra Quattrocento e Cinquecento, in Marco Borella (a cura di), Il Castello per la città , Silvana , Cinisello Balsamo 2004, pp. 73-74

- Andrea Marchesi, Oltre il mito letterario, una mirabolante fabbrica estense. Protagonisti e significati nel cantiere di Belvedere (e dintorni), in Gianni Venturi (a cura di), L'uno e l'altro Ariosto: in corte e nelle delizie, Olschki, Firenze 2011

- Andrea Marchesi, Delizie d'archivio, I, Le Immagini, Ferrara 2015

Fototeca

Related Themes

Compiling entity

- Assessorato alla Cultura e al Turismo, Comune di Ferrara