Ghetto Age

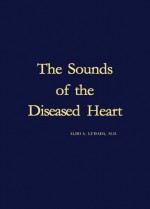

Walled door in Via Contrari. The Jews could not look out of the ghetto. Photograph by Edoardo Moretti, 2015. © MuseoFerrara

The devolution of the Duchy of Ferrara to the Papal State, in 1598, was a moment of strong and substantial change that deeply involved the Jewish Community of Ferrara.

1. The Caesura

The Este, protectors of the Jewish Community, were forced to leave Ferrara in 1598. The last duke Alfonso II died in solitude on 27 October 1597 without a male heir in a direct line to leave the title and the government, paving the way for the application of the bull issued by Pope Pius V Ghislieri on 3 May 1567, Prohibitio alienandi et infeudandi civitates et loca Sanctae Romanae Ecclesiae, which prohibited the investiture of ecclesiastical fiefs – such as Ferrara – to descendants of collateral branches. Alfonso appointed his heir Cesare, son of the"illustrious bastard" Alfonso of the Este branch of Montecchio, an appointment rejected by Pope Clement VIII Aldobrandini. The ‘Faenza Convention’ sanctioned the end of the Este sovereignty: after its signing on 12 January 1598, the young cardinal Pietro Aldobrandini, nephew of the pontiff, entered the city on the 29th to take possession of it. Cesare took the road to Modena – a fief of imperial appointment – passing through the door of the Angels which, as tradition would have it, was closed behind him, to be opened only in the year 2000.

2. The decline

Ferrara, already the capital, quickly transformed into a provincial city, far from the central government, far from Rome. Change also impacted the Jewish community: those who could followed Cesare d 'Este to Modena and Reggio. According to Antonio Frizzi (1848, p. 46) the population census of Ferrara in 1601 revealed the presence of 1,530 Jews compared to 2,000 in 1590. In 1602 the forced transfer of properties belonging to Jews was almost completed, while the pontifical impositions in force during the Este era (such as, for example, the obligation for "Aebrei et Marani inhabitants in Ferrara" to wear "the O in the chest, in yellow") paved the way for the 1624 edict establishing the Ghetto, which took three years to complete. A few hundred families were forced to move into the “Jewish enclosure”.

In the aftermath of the change of government, the new rules had numerous restrictions: in the face of the concession to exercise their activities, Jews were prevented from buying property, from managing duties and taxes, from collecting rents; only one synagogue was tolerated per rite and public funerals were prohibited.

But for the Church, contacts between Christians and Jews were still too evident and frequent, so much so that the Bishop of Ferrara issued the Edict concerning the Jews of the Ferrara ghetto, containing other limitations for Jewish doctors and teachers, for example, who could not exercise outside the ghetto, in addition to the obligation, imposed on at least one third of the Jews residing in Ferrara or passing through (from the age of 12, males and females) to attend sermons with the aim of converting them, held in the Ducal Chapel (currently Sala Estense, in the Municipal Square). Only in 1695 did the Community obtain permission to attend the sermons in the oratory of San Crispino, at the corner of the main street of the ghetto, the Via dei Sabbioni (now Via Mazzini), also to avoid situations of hostility towards the Jews who had previously been forced to cross the square. At the beginning of the new century, in 1703, 328 families lived in the ghetto, living in a serious economic situation: there were 148 merchants who are unable to pay taxes and 72 who lived on alms.

3. Strength

Despite the frequent manifestations of opposition, the repeated attempts of the government to put the Jews of Ferrara in difficulty – it was from 1617, for example, a "religious dispute" between a rabbi and a Jesuit wanted by the legate cardinal Horace Spinola –, unfounded accusations, unpleasant and serious episodes that run between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, weighed down by the edict of Cardinal Tommaso Ruffo of 5 June 1733, the strength of the Jewish community of Ferrara, so well rooted, did not contract. "The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were, despite the ghetto, an era of fervour in the field of studies that saw rabbinical personalities known and recognized throughout the Jewish and non-Jewish world, first of all Isaac Lampronti" (Graziani Secchieri 2012, p. 7).

4. Quotes

"Even for the Israelites the departure for ever of such good and enlightened principles [the Este] was the cause of great pain, the future presenting itself to them full of misfortunes and humiliations, as unfortunately it did not take long to come true, and not a few of those of Spanish origin emigrated from here to Venice". (Pesaro 1878-1880, p. 34)

"Cardinal [Pietro] Aldobrandini appointed with Brief of 19 January 1598 Legate and Pontifical Vicar, took over the Government of the former Duchy of Ferrara. Our fathers begged him to grant them the free exercise of trade, and the allowances they enjoyed under the Ducal regime, and the Legate, after the conclusions of a special Commission on the Jews, promulgated under the 17th of February of the same year, a Constitution, which was called Aldobrandini, in which it was ruled: ‘That the Jews were tolerated in the City and Duchy of Ferrara, on condition that men should wear around the beret or hat a yellow or rancid veil of convenient size, and that women should also wear the same sign, and this by the 24th day of the same month of February. The exercise of all traffic and merchandise was also tolerated, but they were forbidden to buy buildings of any kind, nor to conduct duties or levies, nor to pay rents, nor to give cattle a day or a month; prescribing the peremptory term of five years to sell the properties they owned. They were ordered to restrict their Synagogues to a place and district to be assigned by the Delegate or by the Judge of the Elders, paying for each of them in each year to the House of the Catechumens of Ferrara Ten Chamber Duchies. They were allowed the use of the ancient Cemetery, and the use of those Jewish books that from the Holy Office of Rome were allowed to the Jews of Rome, Ancona and Venice. Lastly, it was ordered that any Jew who had come to settle again in Ferrara or its Duchy to live in the places permitted to Jews, would be obliged to report his name, surname and homeland to the Vice-Legate and Inquisitor of this City within three days, under penalties at the discretion of the Vice-Legate". (Pesaro 1878-1880, pp. 35-36, with citation from Ascoli 1867, p. 16)

"To remove all meekness of government towards our unfortunate ancestors, an Edict of Cardinal Ruffo of 5 June 1733 appeared, which greatly aggravated their position. The sacred books that were their relief in misfortune were severely inhibited, if not visited by the ecclesiastical Censorship; the honouring of the dead with funeral tombs, with tombstones [sic] was forbidden; to sell meat, dairy and other food to Catholics; all licences granted for the mitigation of previous restrictions, in particular by Siman, were annulled; it was forbidden to resort to Midwives , to nurses, to Catholic servants and servants, to go by carriage to the city, to leave it without a license, to trade in objects sacred to Catholic worship; inhibited to Rabbis to wear ecclesiastical clothes, and forbidden to anyone to have relations with catechumens. Very severe penalties would have hit transgressors both Jewish and Catholic”. (Pesaro 1878-1800, p. 53)

Bibliography

- Ascoli, Isacco, Cenni storici sull’origine e sugli avvenimenti risguardanti la Università Israelitica Ferrarese, Bresciani, Ferrara 1867

- Pesaro, Abramo, Memorie storiche sulla Comunità israelitica ferrarese, rist. anast. dell'edizione Ferrara 1878-1880, Forni, Sala Bolognese (Bologna) 1986

- Caniati, Giovanna - Graziani Secchieri, Laura (a cura di), Ebrei a Ferrara (XIII-XX sec.). Vita quotidiana, socialità, cultura, Sate, Ferrara 2012 , pp. 5-8 Vai al testo digitalizzato

Related places

Related Themes

Related Events

Compiling entity

- Istituto di Storia Contemporanea di Ferrara

Author

- Edoardo Moretti

- Sharon Reichel