Baluardo dell'Amore

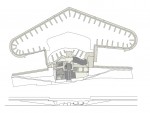

The present-day Baluardo dell'Amore is a true palimpsest of the history of military architecture, starting from the mid-fifteenth-century gate up to the impressive late-sixteenth-century spade-shaped bastion.

Historical notes

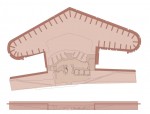

Built into Duke Borso d'Este's mid-fifteenth-century curtain wall (which incorporated the filled-in island of Sant’Antonio in Polesine within the city), the Baluardo dell'Amore (literally the Bastion of Love) as we see it today - with its typical ‘ace of spades’ shape, complete with deep re-entrant sides - was actually added more than a century later. Indeed, it was Alfonso II d'Este who commissioned a major series of works to strengthen the southern fortifications near the River Po between 1578 and 1585, according to plans drawn by engineers and military specialists such as Cornelio Bentivoglio, Marcantonio Pasi, Giulio Thiene and Giovanni Battista Aleotti. In particular, Aleotti (Argenta 1546 - Ferrara 1636) played a leading technical/planning role in the construction of the Baluardo dell'Amore, assisted by two talented foremen: Paolo Roy and Bartolomeo Tristano.

The materials for its construction came from the Castel Nuovo buildings that were being demolished after the destructive earthquake of 1570, from the dismantled former Baluardo dell'Amore and from various local furnaces, including the one near Punta di San Giorgio.

Along the sides of the large bastions built by Alfonso II (dell’Amore, San Pietro, Sant’Antonio and San Lorenzo), there were two defensive orders, called ‘treacherous fire’ because they were hidden from enemy eyes by the curved ramparts. In particular, spade-shaped bastions had ‘open embrasures’ on top and ‘low squares’ bordered by high walls. The artillery, placed both on the sides and on the façades of the ramparts, could then protect the straight curtain walls, flank the faces of the adjacent ramparts, and simultaneously attack in the direction of the front rampart, implementing the most advanced techniques of sixteenth-century warfare (Scafuri 2003, p. 55).

All four of the aforementioned bastions are made up of a dirt rampart about 10 m high, contained by masonry walls measuring 80 cm thick. The perimeter curtain wall is reinforced by perpendicular underground buttresses, also 80 cm thick. The bastion surfaces are vertical in the sections that run parallel to the walls, while they're inclined on all the other sides. In a severe state of disrepair by the time restoration work began in the 1980s and 1990s, serious structural damage was discovered at that time: large external cracks and distortions of the structure of the wall within the embankments, while the salient angles had even greater cracks, especially at the quoin or joint between the protrusion and perimeter masonry and on the vertical and rectilinear sides (Bernardi-Pastore 2003, p. 145).

A road, gate and bastion: what's love got to do with it?

The writings of Gerolamo Melchiorri on the etymology of city toponyms, published in the early twentieth century, offer some insight into the name of the bastion:

This street is called Via Porta d’Amore (Road of Love) because of the ancient gate, called ‘Porta dell’Amore’ (Gate of Love), which must have been created after 1451, when the Island of S. Antonio del Polesine, which included the gate, was encircled by walls. It remained until 1520, closed when the bastion of the same name was built. Fifty years alter, in 1570, the present-day Church of Maria Annunziata was erected at the base of the wall of Piangipane. At the time, the church was called ‘Buon Amore’ (Good Love) because it held a devotional image of the Virgin Mary, which was on the wall of the old gate.

Scalabrini claims that the ‘Porta d’Amore’ or ‘Buon Amore’ name came from the following: at the corner of Via Assiderato (or Desiderata,, meaning ‘desired’ according to the historian), in the street of Porta d’Amore, lived a girl that many young men admired. Having become an orphan after the plague of 1520 and taken care of by a young man who, once the plague ended, took her to the parish priest and the church, swearing that he had always respected the girl. He took her as his wife and, because the rare act was done only for love, the street was called ‘dell’Amore’ or ‘del Buon Amore’ from then on.

Restoration and archaeological digs 2007-2018

In 1936, a two-story building was erected atop the bulwark, used as a nursery school (Bianca Merletti School), taking up a footprint of about 500 square meters. The demolition of that building and the work to retrofit and secure the bastion took place from August 2007 to February 2008. After the aforementioned school was torn down, the static surveys carried out on the newly-cleared grounds brought to light a few historical architectural findings in need of further investigation, done through archaeological digs carried out in 2013 and 2014. These excavations revealed a true palimpsest of military architecture: from the ruins of the old Porta d’Amore (built in 1451), with its turreted shape and adjacent guard-house (both destroyed and buried in 1630), to the traces of the small triangular bastion built in 1557 by Ercole II d’Este to defend the gate.

In the area that was studied (about 650 m2 in total), archaeologists found other buildings, integral parts of the entire fortification, including a casemate with barrel vault ceilings, old floors, a small but interesting oratory and additional light slits in the sides of the bastion.

At the pointed edge of the outer salient angle, there is a late-sixteenth-century hook originally designed to hold a marble shield with the House of Este’s heraldic emblems. During the nineteenth century, it was used as a lamp holder, one of the many positioned along the wall for the customs guards active until 1930.

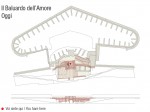

The future of the Baluardo dell'Amore Archaeological Park

The need for practical intervention aimed at reconnecting the various sections of city walls and also the pedestrian permeability of the entire system presented an opportunity to create routes for visitors to the future Archaeological Park of the bastion. Visitors will access the site from Via Baluardi thanks to an iron gate placed between the two curtain walls enclosing the area, already created through a composition of metal cages with the reinforced earth system, in order to restore continuity to the green terreplein of the city walls. At the entrance, visitors will stand before a curtain wall made up of the remains of the fifteenth-century wall, dating to the era of Borso d’Este and the Porta d’Amore. It will rise thanks to a metal structure extending upwards, outlining the original shape. A footbridge will be placed above the curtain wall to connect the sections of the city walls, at the centre of which will be the upper level of the Porta d’Amore. By restoring the continuity of the urban promenade, visitors can enjoy the Archaeological Park from above and enter the upper level of the old tower, recreated spatially.

Visitors can also then enter the park, passing under the Porta d’Amore thanks to the 'rebuilt’ arched opening and upon exiting, they will find themselves before the restored and strengthened ravelin (built in 1557). Springing lines, ashlars and keystones are still visible on the walls of the small bastion, evoking the covering of the ‘tunnel’ that once existed between Borso's walls and the ravelin. The walls of the archaeological elements will be conserved, restored and reinforced, while the entire surface area open to pedestrians inside the park will be given a new cement covering designed to evoke the original flooring found within the structure.

Bibliography

- Gerolamo Melchiorri, Nomenclatura ed etimologia delle piazze e strade di Ferrara (1918), a cura di Eligio Mari, Liberty house, Ferrara 1988

- Rossana Torlontano, Il sistema fortificato di Ferrara prima della costruzione della fortezza del papa e il ruolo di Giovan Battista Aleotti in Opus. Quaderno di storia dell'architettura e restauro, 6 1999

- Maurizio Bernardi, Michele Pastore, Il restauro delle Mura: gli interventi, in Maria Rosaria Di Fabio (a cura di), Le mura di Ferrara. Storia di un restauro, Minerva, Bologna 2003

- Francesco Scafuri, Le mura di Ferrara. Un itinerario attorno alla città, tra storia ed architettura militare, in Maria Rosaria Di Fabio (a cura di), Le mura di Ferrara. Storia di un restauro, Minerva, Bologna 2003

Fototeca

Related Themes

Related places

Compiling entity

- Assessorato alla Cultura e al Turismo, Comune di Ferrara